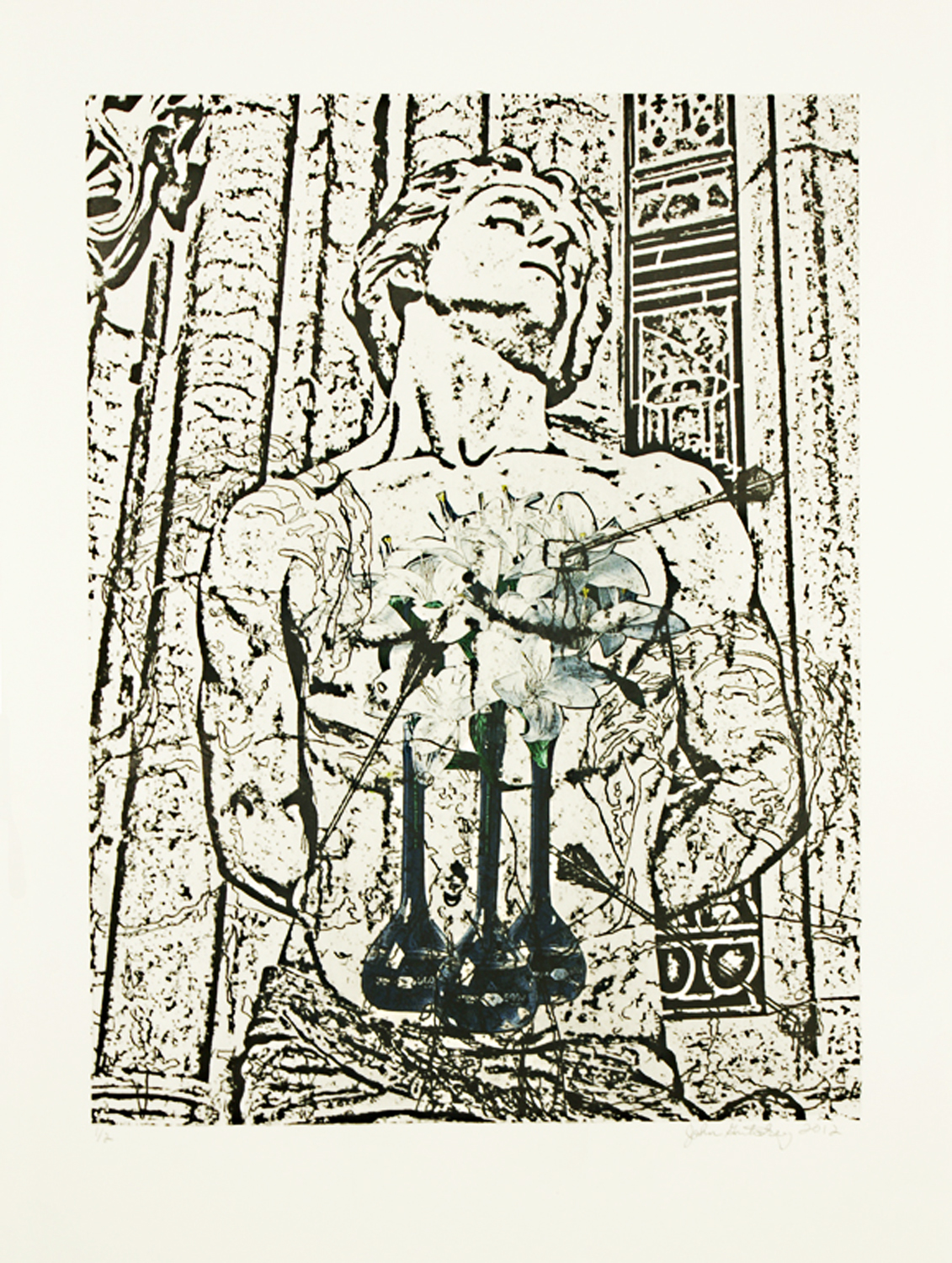

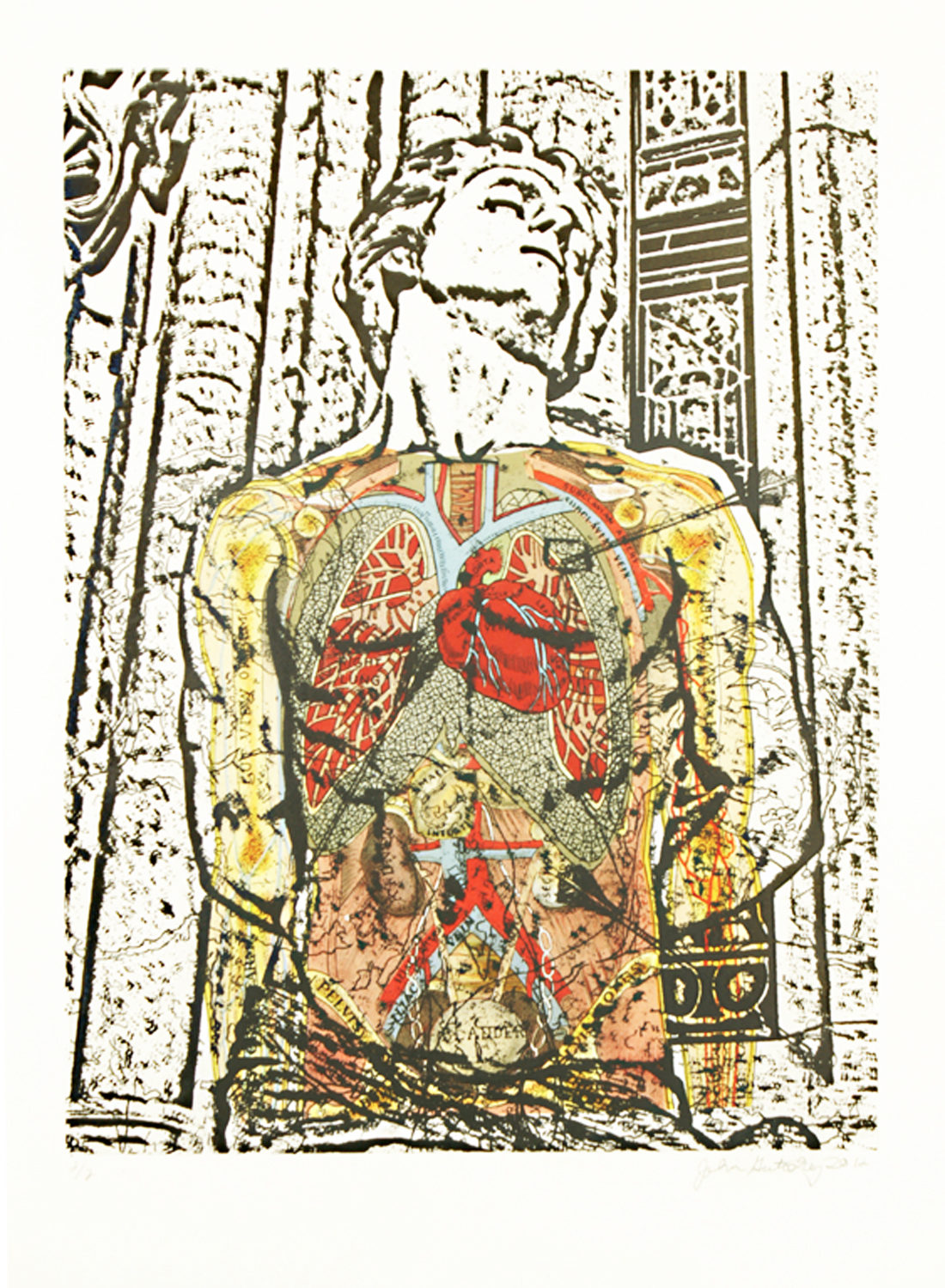

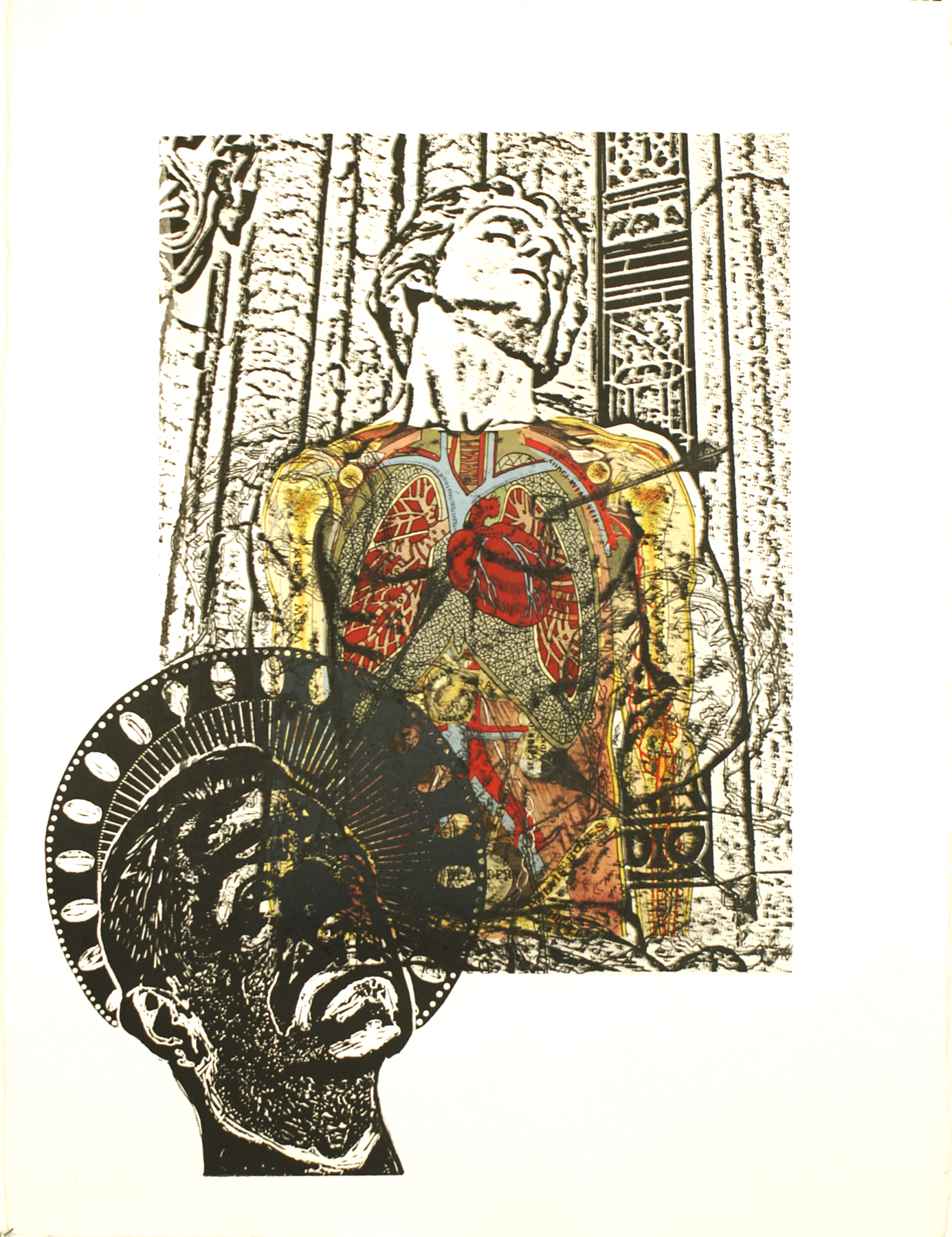

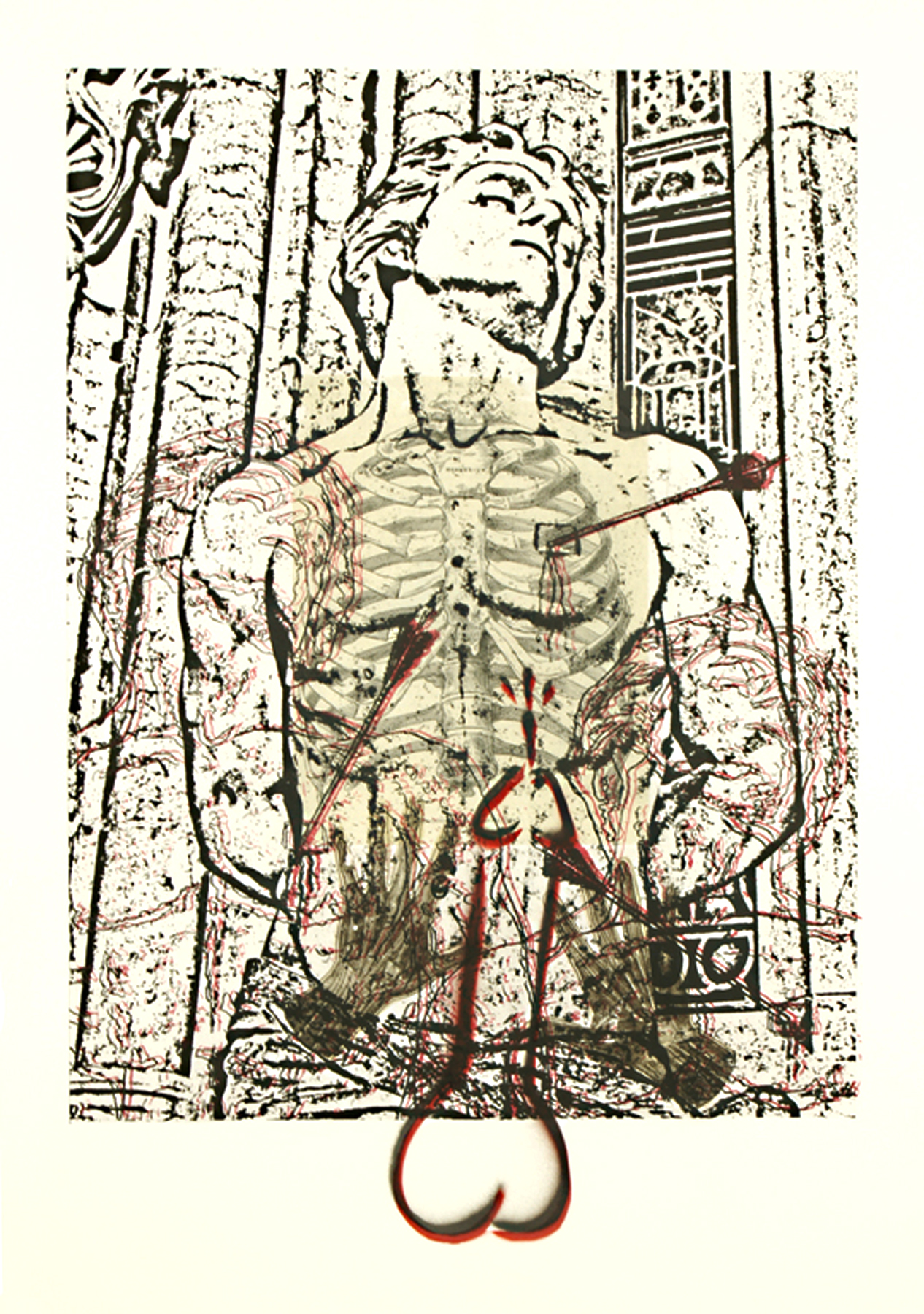

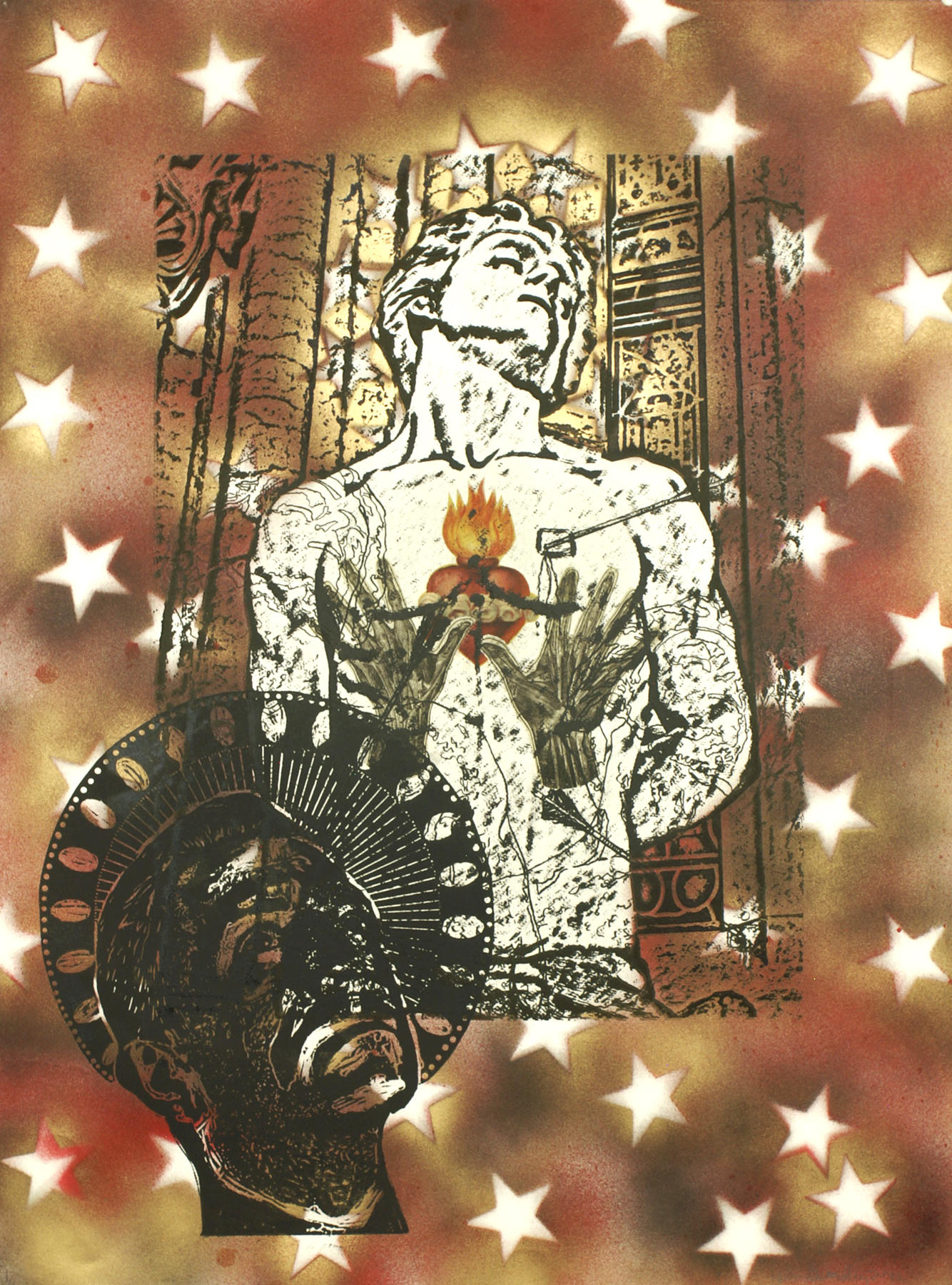

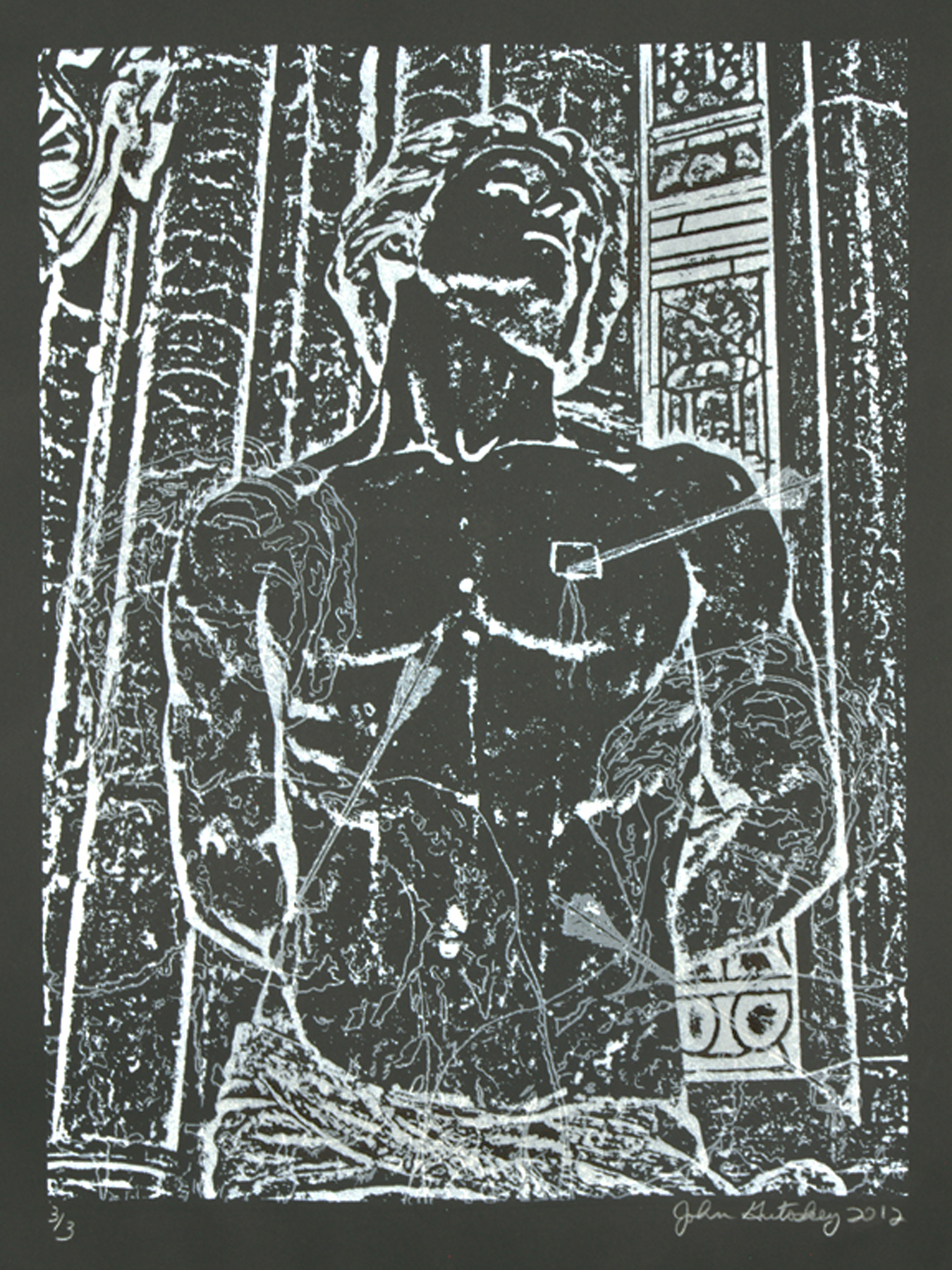

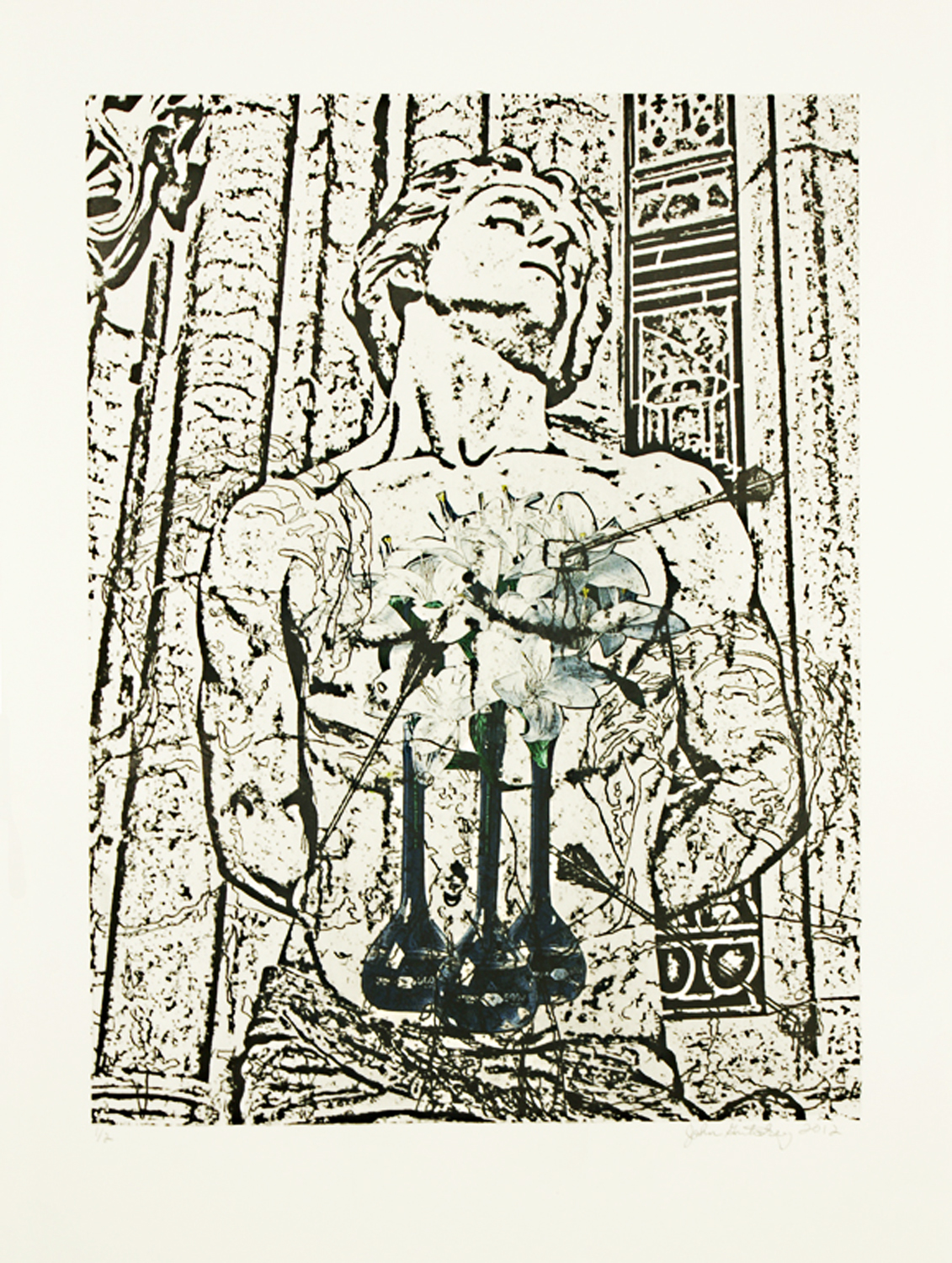

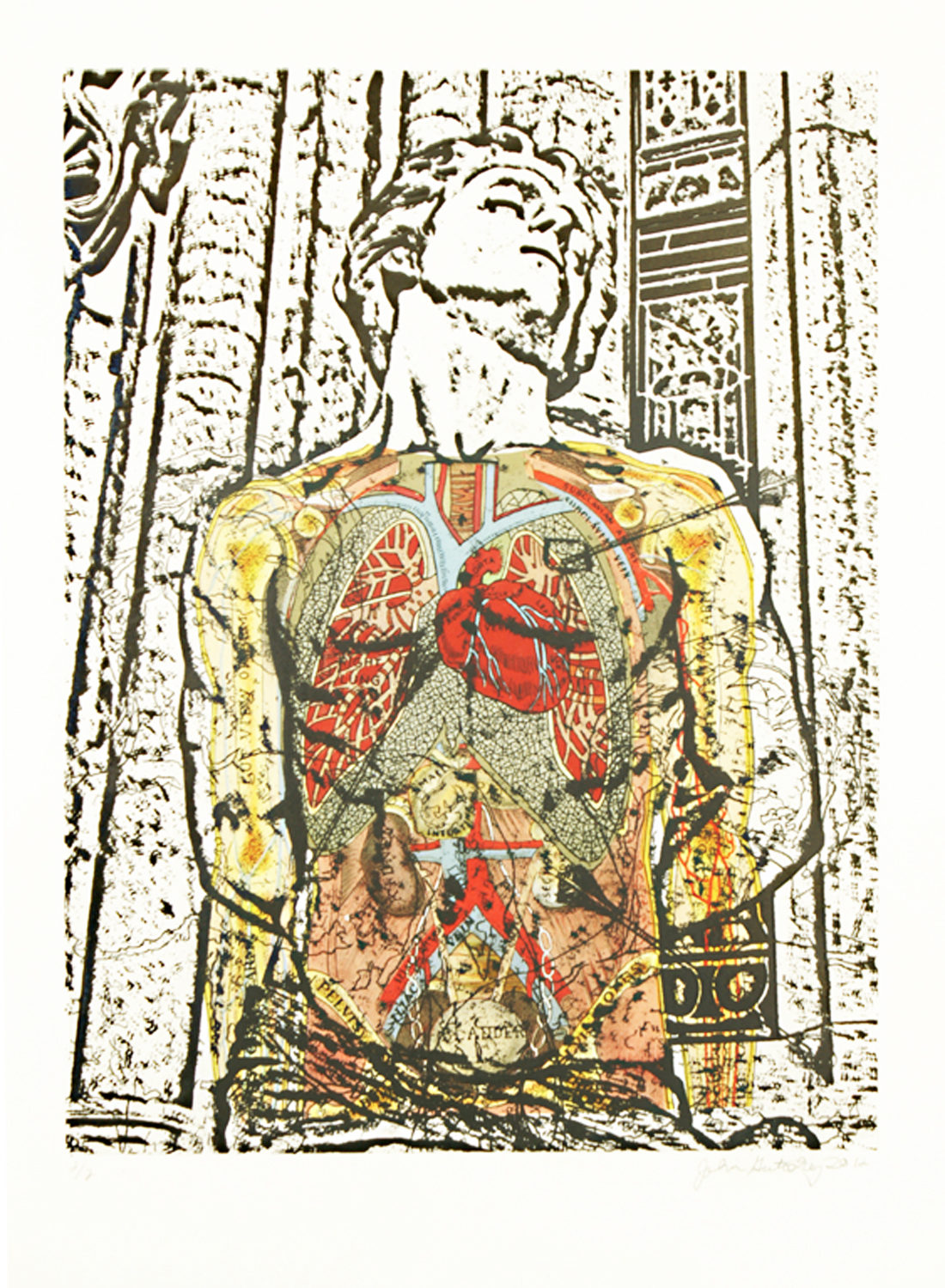

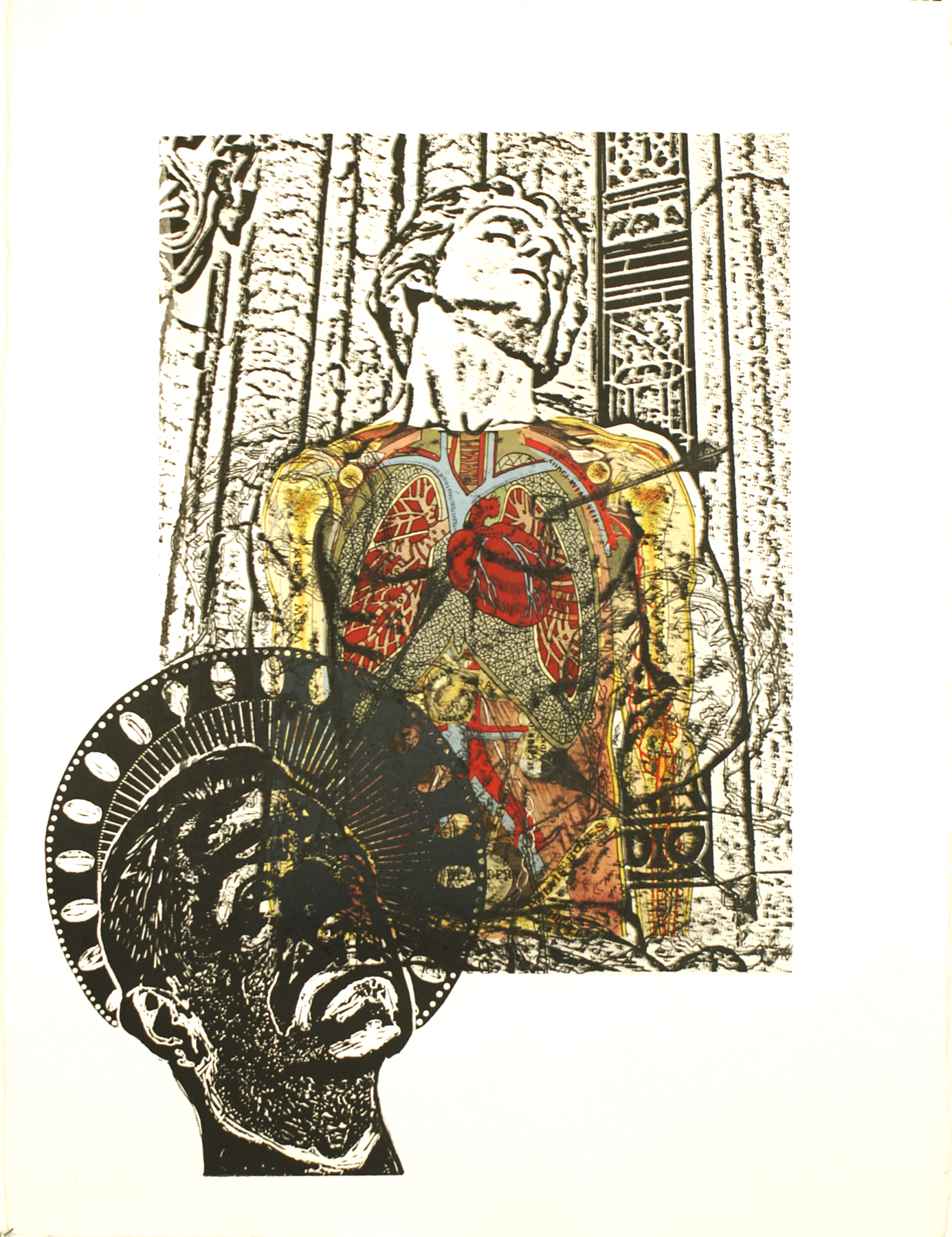

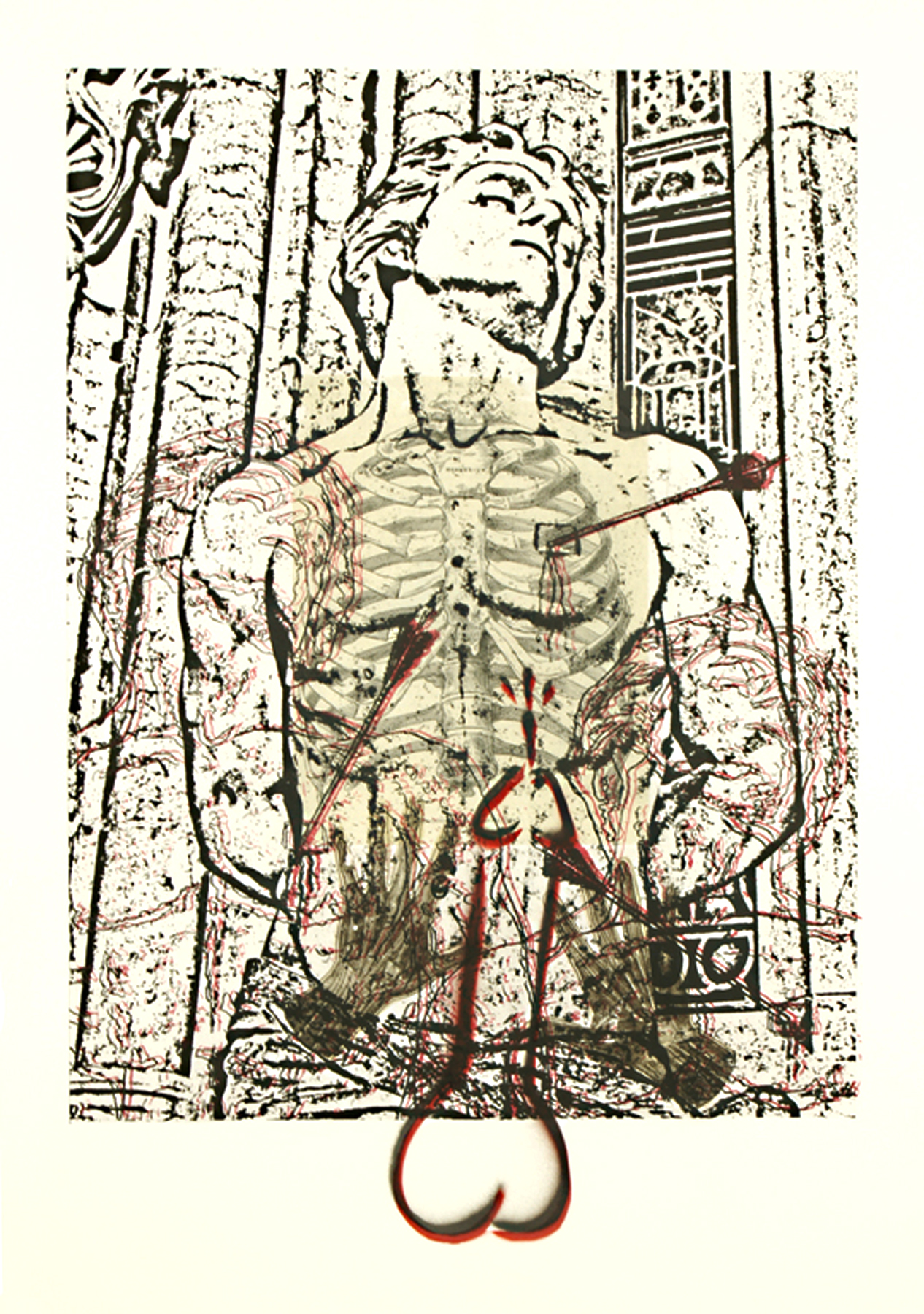

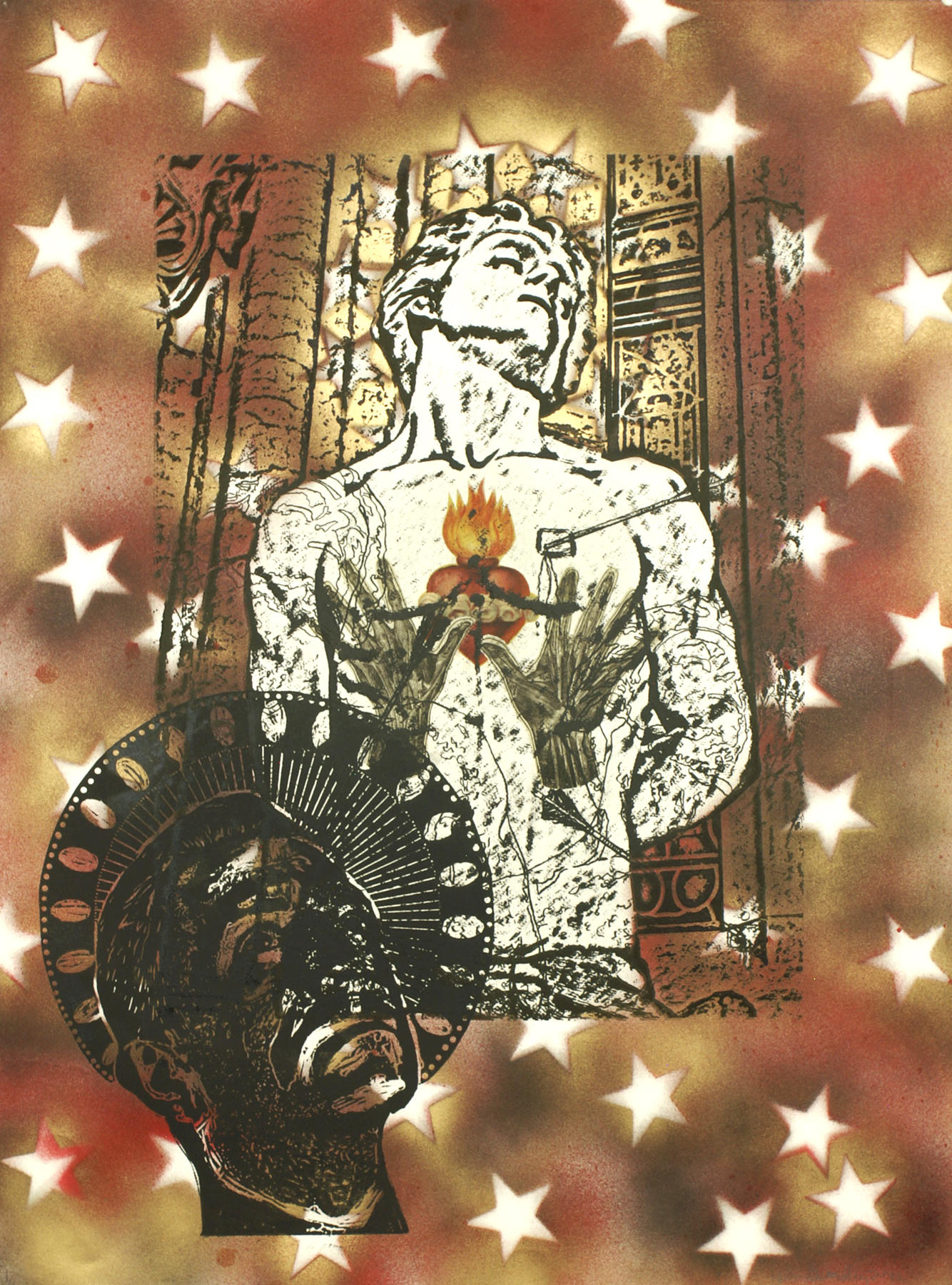

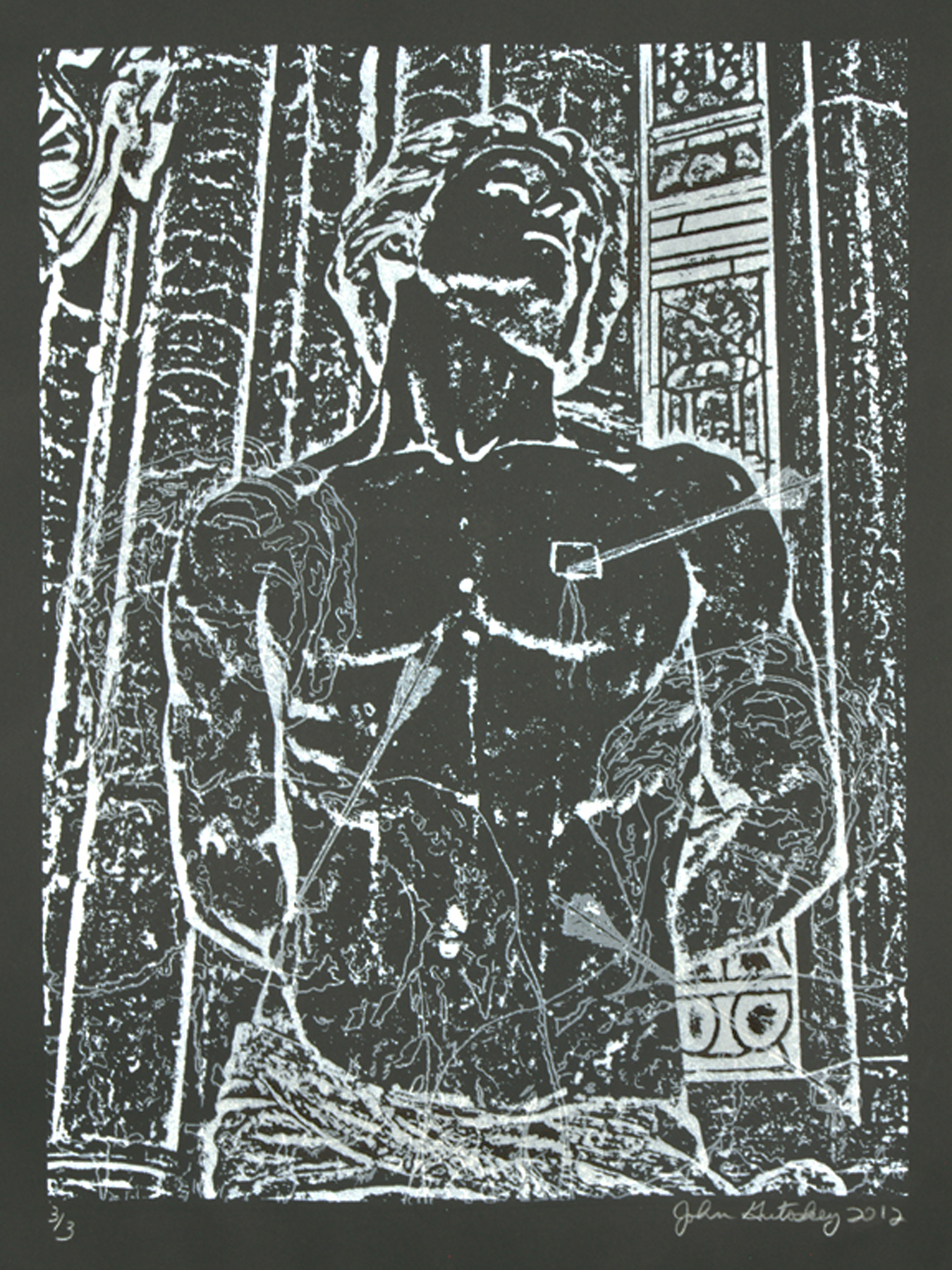

I applied concepts around the construction of identity to a series of prints I made with a photolithographic image of St. Sebastian based on a photograph I took of a sculpture of St. Sebastian that is in the Lisbon Cathedral in Portugal. After having worked with what I considered to be more nostalgic kinds of taunts–taunts that have lost some or all of their ability to offend–I started to use some of the more sexually graphic taunts that were composed with more offensive language and laced with threats of violence and anger at my perceived queerness. I worked in layers with image and language on this series of prints. I would apply the words and then overprint and bury them and then try to excavate them back up to the surface so the words would look old, worn, distressed, and a bit harder to make out. I attempted to make some of them look like they had been defaced or graffitied. I brought in a variety of other print mediums to make a series of hybrid prints that were multi-layered. I brought in other visual representations of taunts like some of the gay slang derived from flowers like pansy, lily, or roses, as well as anatomical images, halos, hands, stars, and other references to religion and transcendence.

I was interested in visualizing how abjection or an abject position can lead from shame and suffering to transcendence–as with the Christian saints. St. Sebastian is an image I have come back to repeatedly in different media since the early 1980‘s. It is an image that I can trace back to my childhood in a Polish Roman Catholic family. Because St. Sebastian was believed to ward off the Black Plague, his image is found in some form in most Christian churches. Outside of images of Jesus Christ, St. Sebastian is the most reproduced male figure in art. He was a soldier and an athlete and was typically portrayed as a beautiful, muscular young man with little covering his naked form beyond a loin cloth. He is usually tied to a column or tree and shot through with arrows. His face is often shown with an expression of agony on it.

Because these images can be perceived or read as homoerotic, this expression of agony can also be read as an expression of sexual ecstasy. This negotiated or oppositional reading of St. Sebastian as a gay icon in sexual ecstasy is way to apply Sedgewick’s concept of an anti-homophobic analysis. Because of his supposed ability to ward off the plague, as well as the homoerotic subtext–his image was appropriated by many gay artists during the AIDS crisis of the 1980‘s and rewritten and reread as queer. St. Sebastian is another example of a high straight cultural icon and symbol brought low through queering and turned into a gay icon and symbol.

St. Sebastian’s image has often been used by gay artists to suggest an abject or deviant homosexual figure, and how that sense of being abject reflects the life experiences of so many gay men. His image was a way for me to address Michael Warner’s writings about the discourse of shame and abjection, and how this binds the gay community together in their shared experience of abjection. St. Sebastian also served as a symbol of the suffering and death of many talented, young gay artists during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980’s.